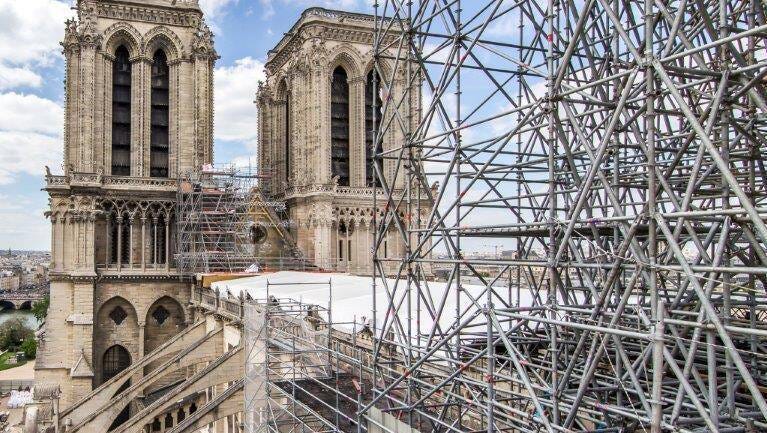

In 2019, a massive fire broke out at Notre-Dame Cathedral, destroying its iconic spire, wooden roof structure and upper walls, alongside other major damage. While the causes for the blaze haven’t be…

Listen to this episode with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Paris Unlocked Newsletter to listen to this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.